|

WAR, TAX CUTS, AND THE

DEFICIT

Center for Budget Priorties By Richard Kogan July 8, 2003 For months, analysts have been saying that the deficit for the current year is likely to hit $400 billion and that the deficit for the coming year, fiscal year 2004, will likely be even higher. Recently, the Congressional Budget Office confirmed the first of these fears, writing, "[we now project] that the federal government is likely to end fiscal year 2003 with a deficit of more than $400 billion, or close to 4 percent of gross domestic product.'[1] On April 24, the President said in a speech in Canton, Ohio that the war and the recession caused those deficits. He declared "Now, you hear talk about deficits. And I'm concerned about deficits. I'm sure you are as well. But this nation has got a deficit because we have been through a war.' Three sentences later, the President added: "And we had an emergency and a recession, which affected the revenue growth of the U.S. Treasury.'[2]

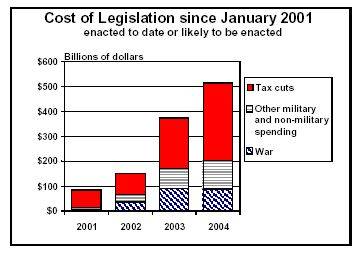

Yet the cost of war, though by no means trivial, is responsible for only a small share of the deficits we face. The President's tax cuts are a much more significant cause. Congressional Budget Office data indicate that in 2003 and 2004, the cost of enacted tax cuts is almost three times as great as the cost of war, even when the cost of increases in homeland security expenditures, the rebuilding after September 11, and other costs of the war on terrorism — including the action in Afghanistan — are counted as "war costs,' along with the costs of the military operations and subsequent reconstruction in Iraq. Table 1 provides the budget data that documents this fact.

The President's Canton speech is striking in several other respects, in addition to his blaming the war for the current deficits.

* The President declared that "the minute I got sworn in, we were in a recession. And that's why I went to Congress for a tax package.' The first sentence is not accurate. The recession dates from March 2001; both the economy and the number of jobs continued to grow through March. (The number of jobs has shrunk steadily since then.) Moreover, the President's own economic advisers — and the budgets he presented to the nation in February and April 2001 that contained his tax cut — projected continued healthy economic growth: 2.4 percent for 2001 and 3.3 percent for 2002, for example.[3] * How about the President's claim that he requested his tax cut because of the (pending) recession? The tax-cut package the President requested early in 2001 was virtually identical to the tax package he had campaigned on for more than a year, during boom times. It strains credulity to believe that the tax package he first unveiled in 1999 when he was facing Steve Forbes and John McCain in the Presidential primaries was designed to respond to a recession that started in March 2001. * In his Canton speech, the President also blamed Congress for phasing in the tax-rate reductions, estate tax repeal, and other aspects of the 2001 tax cut that he signed into law. After saying that he went to Congress for his tax package because the minute he was sworn in, we were in a recession, the President continued: "And Congress responded, but the problem is they responded with a phased-in program. They said tax relief was important and tax relief should be robust, but they phased it in over a number of years — three years in some cases, five years in others, and seven years. Listen, all I'm asking Congress to do is to take the tax relief package they've already passed, accelerate it to this year so that we can get this economy started and people can find work.' The President is re-writing history here, as well. It was the President who asked Congress to phase in most of the tax cuts over five years, both when he first unveiled his tax-cut plan in 1999 and again when he laid it out in detail in his first budget, in February 2001.[4] (Moreover, it was Congress, not the President, that accelerated the creation of the new 10 percent income-tax bracket into 2001, thereby creating the $300/$600 "rebates' to respond to the slowing economy.) * In his Canton speech, the President stated that the first way to deal with the deficit is to "increase revenues to the Treasury through economic growth and vitality.' His budget and the congressional budget plan call for major additional tax cuts, however, causing revenues to decline rather than grow, relative to current projections. His own budget acknowledges this; it shows that his tax cuts will increase the deficit substantially, not reduce it.

Revenue losses from new tax cuts are inevitable unless the tax cuts would somehow trigger so much economic growth that the Treasury would collect more revenues than it would otherwise have done. No reputable analyst believes this will occur; history and economic analysis demonstrate conclusively that cutting taxes substantially results in large reductions in revenues. Indeed, this year's Economic Report of the President, which President Bush signed, states that "although the economy grows in response to tax reductions (because of higher consumption in the short run and improved incentives in the long run), it is unlikely to grow so much that lost revenue is completely recovered by the higher level of economic activity.'[5] In addition, an impressive array of analyses from the Congressional Budget Office, the Joint Committee on Taxation, the Committee for Economic Development, economists at the Brookings Institution, economists at the Federal Reserve Board, and other analysts and institutions have concluded that the tax cuts proposed now or enacted in 2001 will have only a small effect on long-term economic growth, that these small effects on growth could be either positive or negative, and that the tax cuts will cause large increases in deficits.[6] End Notes: [1] Congressional Budget Office, Monthly Budget Review, June 9, 2003. [2] Statement of President Bush at the Timkin Company, Canton, Ohio, April 24, 2003, p.7. Text available at http://www.whitehouse.gov/news/releases/2003/04/20030424-3.html. [3] Budget of the United States Government, OMB, April 9, 2001, page 239. These rates represent the predicted rate of real (inflation-adjusted) growth of GDP over the course of the calendar year. Actual economic growth proved to be 0.3 percent in 2001 and 2.4 percent in 2002. [4] See OMB, A Blueprint For New Beginnings, Feb. 28, 2001, page 194, and Joint Committee on Taxation, JCX-31-01, May 4, 2001. In the President's 2001 budget proposal, no tax cuts were effective in 2001, most tax cuts were phased in over the period 2002 through 2006, and the repeal of the estate tax was phased in gradually through 2010. [5] Economic Report of the President, February 2003, page 57/8. [6] See Administration's Economic Growth Claims Disputed by Broad Range of Economists, Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, April 17, 2003. Also see Kogan, Will the Tax Cuts Ultimately Pay for Themselves? and Will the Administration's Tax Cuts Generate Substantial Economic Growth, both Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, March 3, 2003. Commentary: |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||